Guy Debord wrote a remarkably prophetic book. In its original French, it was titled La société du spectacle. It is something of a sin to discuss this book without speaking French. I don't think it's a prerequisite to understand the ideas behind the text, but to really grasp the language, phrasing and meaning of this great book, fluency or near fluency is likely needed. Fortunately, I feel like writing about it and it's my blog, so I'll do whatever the fuck I like.

This is the first blog post I'm writing in a series I'm calling "One Great Insight". I've often found that many texts, especially great texts, are packed with hundreds of insights. We lead busy lives and the attempt to inspect and understand them all can be overwhelming and unpleasant, so I made a rule. For each book, essay, text or dissertation I read, I try to extract one great insight, that I find myself thinking about constantly. Something really beautiful and clear.

The background to this great insight

I've spoken with friends about this book. Outside of the French speaking world, it does not seem to have taken ahold in quite the way such a profound text usually does. Debord's name rarely appears in the angsty writings of teenagers calling for revolution against a system they barely understand.

Debord was a remarkable French writer and filmmaker who pioneered the Situationist movement. I won't go too deeply into what this movement meant, but it was obsessed with the reclamation of what it deemeds "authentic moments". Situations, in this context, were moments, expressly designed to encourage authentic experience and break through the illusion of modern life. To disrupt our minds tendency towards passivity, and therefore awaken us to how much of our experience has been hijacked by modern "images".

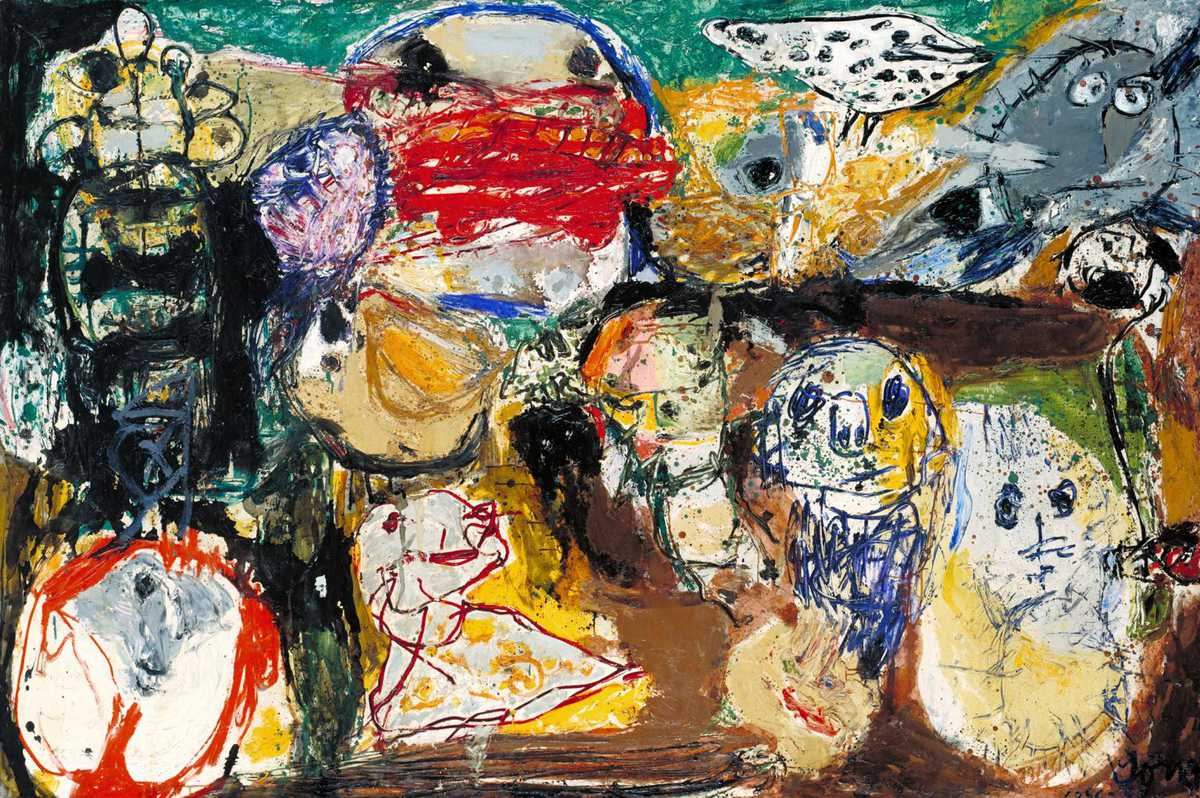

They were deeply entrenched in anti-capitalist thought. Famously, staging performances in the street, or adding prompting questions around supermarkets to disrupt the typical shopping experience. They did this because they perceived something profound about the way advanced capitalism worked. The above painting is argued, by some, to be a Situation unto itself.

Asger Jorn cleverly composed the painting as the antithesis of classical styles. Where a more traditional painter may construct their works to guide the eye, to deliver the beauty to the viewer, to tell a story in canvas, this painting does none of that. It provides enough detail for our minds to recognise a pattern, but it does nothing to explain that pattern. The faces have different emotions, but there is no clear cause. They're painted in colours, ranging from blue to bright red. Why? The honest answer is this: Fuck you, that's why.

Jorn's point, the whole idea of the piece, is to force us to stop and participate in the painting for a moment. I remember staring upward at the roof of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. It was beautiful, but beyond that, I did not feel my brain work. I took it in, I moved on. When I look at this painting, when I attempt to decipher it, when I'm frustrated when I can't find anything, I am no longer perceiving the painting. I'm not just looking at it, I'm engaging with it.. When I turn my attention in this way, there is no mediator. The piece is supposed to make us realise that we spend most of our time on autopilot, perceiving the images that do the work for us.

Reclaiming the means of production

When Marx & Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto (and Das Kapital), they discussed, at length, the function of capital and the role of the Means of Production. That is, if you own a factory, and the workers toil in that factory without a share in the profits, instead paid a wage, then you own the means of production and hold the workers to ransom. Marx's solution to this was for the workers to unite and reclaim the capital for themselves.

But what struck me was that this image, when I found it online, was available if I paid the royalties. I can use it for critique all I like, but the thought of selling something like this strikes at the heart of Debord's central point. In Debord's mind, capitalism has moved to a new arena. In its search for new products, it has expanded out of the means of production and into the means of consumption. This is the great insight I want to discuss. The role of capitalism in our ability to enjoy ourselves.

From Marx to Debord

As capitalism has expanded, Guy Debord made two remarkable observations. First, is that the economy is a self-sustaining, self-defending thing. We think that the economy is a product of our actions, some vast system that emerges out of the choices we make, a reflection of our relative success and failure. Debord disagreed with this. In his mind, the economy was an active thing, that had grown beyond the leash of its masters.

"The economy transforms the world, but it transforms it only into a world of the economy"

To illustrate this, let us think back to the past few months of American politics. Donald Trump has enacted a series of sweeping tariffs. Trump does not have another term to worry about, nor does he have party infighting to concern himself with. He has a comfortable majority with which to pass laws, and he has the liberally applied executive order when the apparatus of American politics is moving too slowly. He seems very much in control, and yet, he has made a number of backwards steps.

One might look at this, as the economy driving our behaviour. In other words, the prospect of economic downturn was enough to force Trump to row back on his policies. He has since taken a much more moderate position. In other words, the economy has mastered us. Economic downturn is bad for everyone, but not simply for fiscal reasons, leading to our second insight.

"The reigning economic system is a vicious circle of isolation. Its technologies are based on isolation, and they contribute to that same isolation. From automobiles to television, the goods that the spectacular system chooses to produce also serve it as weapons for constantly reinforcing the conditions that engender 'lonely crowds'"

A good friend of mine lives in Australia. When he returns to the UK and we meet up, he says how good it is to speak to us, to finally see us after so long. We speak on video call, on the phone and over WhatsApp messages daily, and yet when we meet, we become aware of just how long it has been since we spoke without a mediator. In other words, a product (no doubt a well intentioned product), has placed itself between us to such a degree that it is only when we see one another, and experience an authentic moment together, that we realise how unsatisfying a video call can be.

Those authentic moments snap us out of a haze. This haze is like a space around us, a bubble, that prevents us from connecting with one another in a meaningful way. One need only look to social media to see this in its purest form. Regular people in their 20s, carefully curating every single image on that Instagram profile, to convey a message. To reflect an image, or as Guy Debord puts it, to take part in a spectacle.

"The individual no longer directly experiences his own life, but rather views the spectacle of his life as a detached observer"

The great insight and practice that I derived from this book, beyond the intellectualism around capitalism and the need for a great revolution (of which I find myself still a fervant sceptic) is to live meaningfully.. It is very easy to fall back into a haze, and allow products to fill the void that is left. It is easy to settle for a meagre representation of reality, mediated by social media and TV shows.

To break this, we need to do something brave. We need to construct a situation. When I began to learn Arabic, I used Duolingo. It's okay, it really helped me develop my reading skills with Arabic script, but after a few months, I was bored. After some thought, an idea came to me. I'm going to arrive at a Lebanese restaurant (there was one in Belfast, close to my old house), and speak Arabic and see how far I can get. I walked in, said half a phrase and immediately stumbled over my words. Humbled, I switched back to English. The owner, however, continued in Arabic, and taught me some new phrases.

It was embarassing, but when I got home, the energy was there to continue learning. I remember the smile on the restaurant owner's face when I finally got my sentence right. The cigarette harshened laugh he let out when I finally understood his meaning. The pat on the back he gave me when he told me, betraying the Arab tendency to be polite and warm in all cases, that my Arabic is "very good", after I failed to complete a sentence. These authentic moments, constructed with intention, carry the potential for a kind of insight no image can deliver.